Feb 07 2017

Burroughs Book Finally in Print

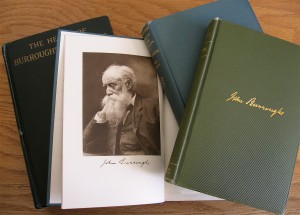

At long last, the Burroughs book is in print. I’ve been reading his essays for decades, and toying with the idea of selecting and publishing excerpts from his work for nearly that long. He wrote over 30 books on nature. I’ve been crazy enough to read most of them.

At long last, the Burroughs book is in print. I’ve been reading his essays for decades, and toying with the idea of selecting and publishing excerpts from his work for nearly that long. He wrote over 30 books on nature. I’ve been crazy enough to read most of them.

The full title of this book is Universal Nature: Philosophical Fragments from the Writings of John Burroughs. As the title suggests, the excerpts I have selected tend towards the abstract. While Burroughs was the master of the quaint nature essay – quite often writing about songbirds – he delved deeply into philosophical matters as well. In his later years he became interested in the tension between science and religion. His was an utterly naturalistic worldview, of course, so he leaned as heavily towards pantheism as I do. Hence my obsession with him.

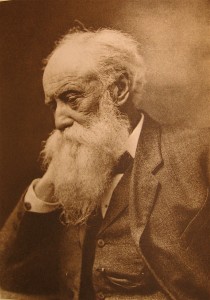

While Burroughs comes off as a simple, white-bearded countryman observing birds and the like, he was a surprisingly complex character in real life. My biographical introduction puts his work in context, showing how his thoughts emerged from friendships, travels and fruit farming in addition to extensive reading. The excerpts are organized chronologically, making it clear how his perception of wild nature evolved over time from the particular to the universal.

You can get a copy by going to my website WoodThrushBooks.com. It is also available at Amazon. I hope you find the natural philosophy of John Burroughs as intriguing as I have.

Comments Off on Burroughs Book Finally in Print